“Every citizen in this country needs to see this film”: Jazz Money’s lyrical documentary “WINHANGANHA” screens in North Sydney

WINHANGANHA, directed by poet and director Jazz Money, was screened in North Sydney as part of the Gai-mariagal Festival. It is available to watch for free during NAIDOC week via streaming service DocPlay.

The North Shore is currently abuzz with Gai-mariagal Festival events, from workshops to guided walks, to film screenings and much more. The festival, which started on National Sorry Day (May 26) and runs through to the end of NAIDOC week (July 13), seeks to promote First Nations culture and history.

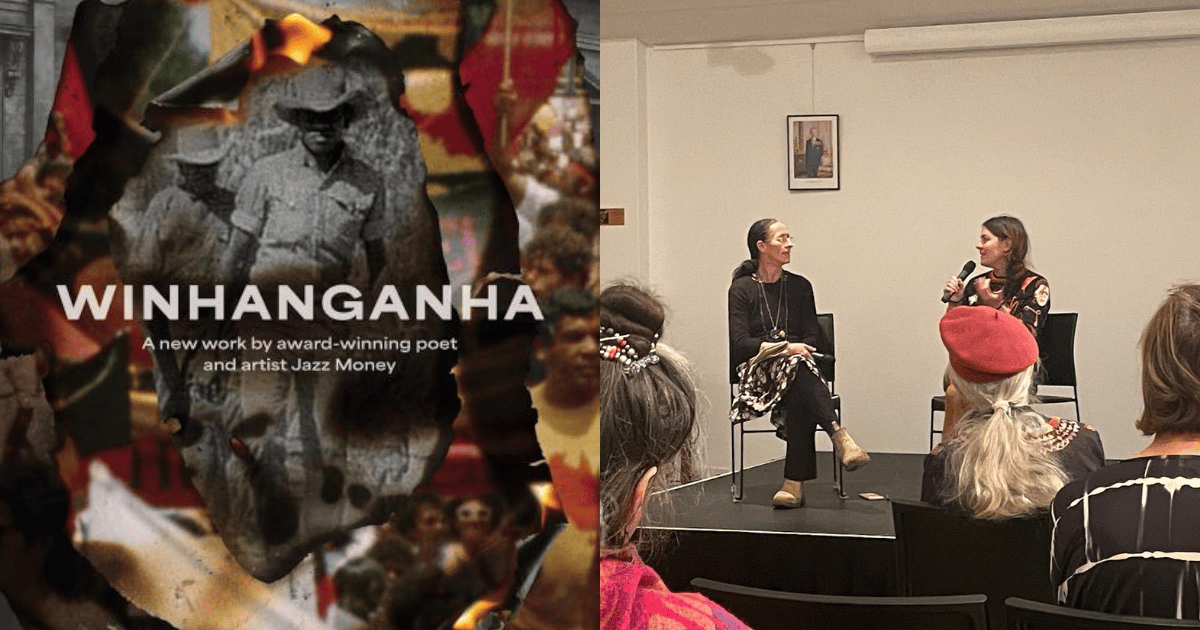

On Thursday, the North Shore Lorikeet attended the festival’s screening of Wiradjuri artist and poet Jazz Money’s film WINHANGANHA, a word which loosely translates as “to know, think, remember”. The screening was held in the Fred Hutley Hall in the North Sydney Council chambers on Cammeraygal land.

Jane Stanley, Assistant Curator at the National Film and Sound Archives (NFSA), explained in her introduction that the poet was given access to the NFSA’s archives to respond to the question “who are we now?”

Money crafted the film, the first feature film ever made from NFSA archives, from a staggering 191 hours of material using what she calls a “magpie approach”.

With an original score by Filipino-Aboriginal rapper and composer DOBBY (Rhyan Clapham), the film stitches together archival footage in ways that resonate lyrically and to shocking effect, calling to mind the politics of Pat Fiske’s 1998 Australia Daze and the impressionistic style of Anne Pratten’s Terra Nullius (1992).

It was hard not to notice the portrait of King Charles hanging next to the screen throughout the viewing.

The film has five chapters, each opened with a poem authored and spoken by Money, setting the tone for the chapter ahead and gently guiding the audience.

“In a way, they’re like five short films which all speak to each other,” Money reflected.

The overarching thesis of the film is about the body as an archive, and there’s no doubt that WINHANGANHA is partly a film that interrogates the ways the bodies of First Nations people have been viewed by colonisers - and brutalised - since the tall ships arrived.

Money cautioned attendees before the viewing that the second chapter, in particular, is quite heavy. Indeed, some in the audience visibly flinched throughout this chapter which depicts incidents of police brutality and a profoundly disrespectful approach to an Indigenous burial cave.

“But this is also a film about love, strength, and protest,” Money emphasised. “We don’t get to see our love and our joy celebrated often enough.”

Other chapters display the ingenuity, weaponry, impressive physicality and athleticism of Indigenous Australians as well as the beauty and power of communities’ ceremonies. Anger, protest, and resilience also emerge as themes - as well as the brazen ignorance of some non-Indigenous people.

In one striking segment, a non-Indigenous man’s voice narrates over footage of an Aboriginal man making a fire, imperiously stating that “they don’t understand friction… but they use it to generate heat”.

This line stood out to Muruwarri-Wiradjuri woman Tammi Gissell as well, who commented afterwards on the irony of it gobsmacking her.

“It’s like: by your very own language and admission, you are a fool,” she said.

Gissell, the First Nations Collections Coordinator at Powerhouse Museum, replaced Nathan “mudyi” Sentance at the last minute and proved a spirited moderator.

Gissell was visibly moved and shared a long hug with Money right after the screening.

When Gissell said that she found the film “so choreographic, like an opera for all my senses,” Money smiled, explaining it was her intention that her work have the energy of a music video.

“I wanted it to be a dance film initially, because the body as archive is what the film is about. It moves from profiling the body alone to bodies together as a collective.”

“I think every citizen in this country needs to see this film,” Gissell said.

Mayor Zoë Baker told the Lorikeet after the event that North Sydney Council is committed to “fostering respectful and meaningful relationships with First Nations communities.”

“Through ongoing collaboration and cultural celebration, we continue to walk together on a journey of truth-telling and reconciliation,” she said.

“Our screening of WINHANGANHA offered an opportunity to reflect, learn and connect through the powerful medium of film, and conversation.”

The process

“The majority of this collection is painful,” Money elaborated during the post-screening Q&A, saying the strength to persevere came from the strength modelled by those she encountered in the archives.

The process was painful in another way, too. Money said she had to go through an elaborate rights clearance process that ultimately cut down her film, which clocks in at 64 minutes, by a third.

Some of the post-screening discussion interrogated the usefulness of such Western methodologies of archiving and the ways the film is a way of “challenging the knowledge authorities … with acts of creative revolution”.

During the discussion, Gissell and Money agreed the story told in WINHANGANHA and the larger story about relations between First Nations people and non-Indigenous Australians is “a shared story – and a shared responsibility.”

“It’s not my film,” said Money.

Since its release, the artist has had people approach her to tell her how much it means to them – and that they were even present at some of the events depicted.

“You’ve got to let your community be proud of you,” Money said of this response.

WINHANGANHA has screened across the country since its release in 2023, and globally at the USA’s Smithsonian Institution and Harvard University, and even as far as Nuremberg’s Filmhaus.

Jazz Money’s books, the latest of which is a children’s picture book called The Frog’s First Song, were sold at the event by Crows Nest bookshop Constant Reader.